The Piece of Furniture

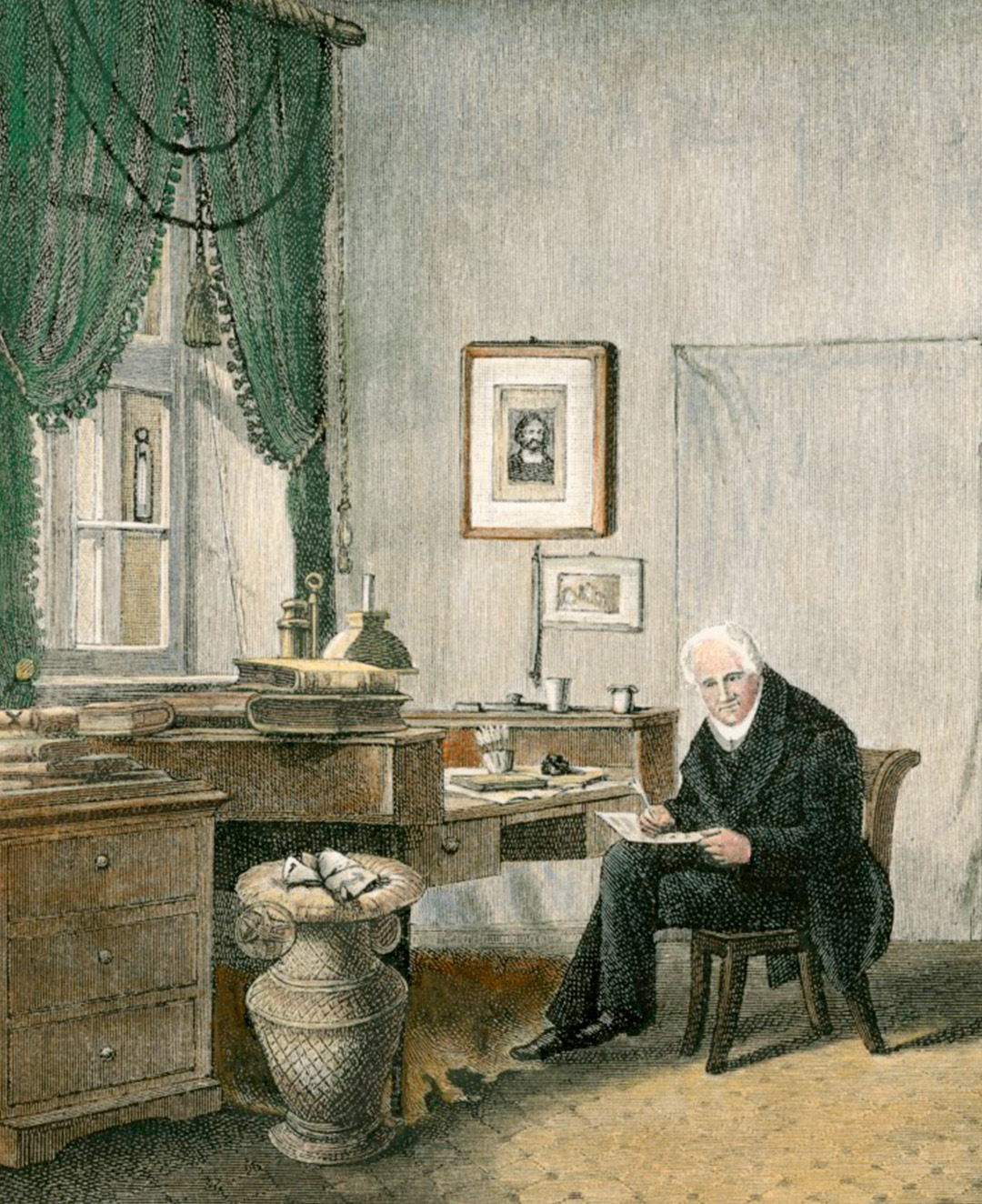

A table made of wood and brass – neither baroque nor heavy but of engaging simplicity. On slender legs with elegant wheels, as mobile as its owner. This is what Alexander von Humboldt must have needed when he returned to his hometown after a youth marked by restlessness and wanderlust, his spectacular five-year expedition to the primeval forests of America, the peaks of the Andes and the high plateaus of Mexico, and after long years in Paris. Not only as the most famous Berliner, which he probably still is today, but as the most famous person of his time, worldwide, after Napoleon.

In 1827, he did not give the task of creating a perfect piece of furniture to prepare the ground for further great deeds to one of the stars of artistic carpentry – of which there were several in Berlin. He commissioned a master who knew how to implement the ideas and needs of the illustrious client without any vanity of his own. The name of the cabinetmaker has been lost to posterity, but the precision craftsmanship and simple elegance with which he created a space for the great polymath’s future ideas is timeless.

Alexander von Humboldt did not need a desk of monumental weight in his Berlin flat in Oranienburger Straße; he did not need it to emphasise his social consequence. The fine brass cut castors, indeed the lightness and mobility of the table, will rather have supported him in continuing to travel in spirit. Amidst maps, mountains of manuscripts, collected natural objects and books, “in my Oranienburg wilderness” – as he wrote himself.

According to his own account, Alexander von Humboldt wrote around 2000 letters a year to his correspondents at this table, “a fine, invisible network covering almost the entire living world”. It was here that he condensed his profound knowledge of many sciences, his dictum “Everything is interaction” and the experiences of an eventful life into his epic work Kosmos – written down in his characteristic upwardly flowing lines, published in five volumes and still read all over the world today.

The shape of his writing table also reveals a secret of his working method: The research literature and working tools are relegated to plateaus on the sides. The covered flat of the table top itself is reserved for the creative process: the countless larger and smaller papers, protected from any draughts by the raised sides, on which Alexander von Humboldt constantly rearranged his notes, excerpts and drafts, finally bringing them together to form his complex scientific narratives – a masterpiece of organisation and overview, supported by a cleverly and functionally designed piece of furniture.